Tuesday, June 16, 2009

Wednesday, June 10, 2009

Abandon all Hope Ye who Enter here

I've been thinking a lot lately about hope. It seems to me that it is always absent in my life, either due to my innate cynicism or the pressures of the outside world. It's hard to have hope when you're constantly in competition with yourself, and everyone else for that matter. It seems we forget about the goal and concentrate only on the means. There's a line that was cut out of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly that was subsequently used as an episode title for Weeds: "If you work for a living, why do you kill yourself working?" It's simple (and quirky) enough to describe my predicament. I wish I could just lay back, watch the world go by and do as I please for the rest of time, but it's never possible. Responsibilities set in with age, dictated by the society in which we live; we must work, we must make money, we must be independent by depending on others. It all seems so pedestrian.

I've been thinking a lot lately about hope. It seems to me that it is always absent in my life, either due to my innate cynicism or the pressures of the outside world. It's hard to have hope when you're constantly in competition with yourself, and everyone else for that matter. It seems we forget about the goal and concentrate only on the means. There's a line that was cut out of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly that was subsequently used as an episode title for Weeds: "If you work for a living, why do you kill yourself working?" It's simple (and quirky) enough to describe my predicament. I wish I could just lay back, watch the world go by and do as I please for the rest of time, but it's never possible. Responsibilities set in with age, dictated by the society in which we live; we must work, we must make money, we must be independent by depending on others. It all seems so pedestrian.Friday, June 5, 2009

The Red Menace.

Yesterday I bit the bullet I had been facing for so long and registered myself with the New York State Communist Party. Difficult as it was, when I returned home that evening I found a package containing a shirt I ordered almost a month ago: tomato red with the word "Communist" silk screened on the chest. Providence or Coincidence?

Now, apparently, I am a communist. Or, at least, as much as one can be in a free market society. But what does this mean? Most people I've told have reacted with horror as if I am going to be brought up before the House Un-American Activities Committee, but the whole ordeal was hardly as unnerving as I had originally planned for. Three individuals from the party have already contacted me, welcoming me and telling me they were there if I had any questions. In fact, I'm supposed to arrange a formal meeting with someone later this week. It all seems perfectly normal. I guess we'll see.

Thursday, June 4, 2009

Uncivil Disobedience

THEATER REVIEW|'GOD OF CARNAGE'

THEATER REVIEW|'GOD OF CARNAGE'“Children consume and fracture our lives. Children drag us towards disaster, it’s unavoidable.” Michael says in Yasmina Reza’s brilliant new comedy. “Brilliant” is a word I despise, repeated ad nauseum and usually applied to all the wrong things, but there is no other word to describe “God of Carnage”. It was unequivocally the best play I have seen all season, and, to be perfectly blunt, the first play since Kushner’s “Angels in America” that has restored my faith in the theatre. Acerbic, thought provoking, and hilarious, it is all that the theatre is meant to be, and comfortably capitulates to the New York sensibility Broadway should provide.

Originally a French play, produced numerous times in Europe (including one in London starring Janet McTeer and Ralph Fiennes), “Le Dieu de Carnage” as it is called, was translated by Christopher Hampton into English. It tells the story of two bourgeoisie couples who arrange to have a civil meeting after one of their children assaults the other with a stick on the playground. The slick set design offers a cold, modern space suspended in emotion. Bright red walls that stretch up into the sky are revealed when a large white curtain decorated with a child’s crayon-rendered family portrait rises. An oblique, stone wall is in the background. The stage is flanked by two perfect crystal vases filled with white tulips (from the Korean Deli up the street, direct from Holland, $40 for Fifty). Lead by an all-star cast (Marcia Gay Harden, James Gandolfini, Jeff Daniels and Hope Davis) the material is never allowed to rest. Discussions turn to arguments, arguments turn to violence, violence turns to despair all in one tense, Albeesque afternoon.

An obvious devolution occurs with each character (although perhaps not as much with Alan, who is a prick to begin with) and their carefully manicured facades crumble when confronted with the realities of existence. Ms. Harden and Mr. Gandolfini in particular deftly transform on stage as the play progresses. Matthew Warchus’s direction is absolutely splendid; the blocking is obviously very calculated and deliberate but appears effortless, and the special effects (namely projectile vomiting on the part of Ms. Davis, another nod to Albee) are well handled and natural.

As Ms. Reza’s words entertain, they simultaneously subvert societal mores, the role of parents, and the relationships we all have. Her play is fabulous. That’s all. Nothing more.

GOD OF CARNAGE

By Yasmina Reza; translated by Christopher Hampton; directed by Matthew Warchus; sets and costumes by Mark Thompson; lighting by Hugh Vanstone; music by Gary Yershon; sound by Simon Baker/Christopher Cronin; production stage manager, Jill Cordle; production manager, Aurora Productions; general manager, STP/David Turner. Presented by Robert Fox, David Pugh and Dafydd Rogers, Stuart Thompson, the Shubert Organization, Scott Rudin, Jon B. Platt and the Weinstein Company. At the Bernard Jacobs Theater, 242 West 45th Street, Manhattan; (212) 239-6200. Through July 19. Running time: 1 hour 30 minutes.

WITH: Jeff Daniels (Alan), Hope Davis (Annette), James Gandolfini (Michael) and Marcia Gay Harden (Veronica).

Tuesday, June 2, 2009

Day in the Life

Commute: Late train. Arrive in New York at 9:15 for 9:10 class.

Breakfast: Coffee and cigarette.

Class: Art History; discover Courbet and his Realist Manifesto (read.)

Break: Cigarette.

Lunch: Free peanut granola bar from guy on 29th.

Recent purchases: Weeds Season 4 on DVD; Tony Kushner's "A Bright Room Called Day". Both great. Both overpriced.

What's to come: Bio in a medium-security classroom. Work in a medium-security Writing Studio. I hope no one comes in.

What still holds true: I enjoy New York. We'll see when that dissipates.

Saturday, May 23, 2009

Sister, Brother, Teacher, Mother.

It all started about a week ago. Finally finishing up with school, I was headed out for a celebratory lunch with the girls when our professor invited himself along. An odd twist on our plans, but, we went with it and had lunch at Bar 89 (and several other locations). Who knows, maybe it improved our grades. So, I did what any perfectly normal young man would do when going out with a man old enough to be his father: I drank. Three beers, two absinthe and a shot of tequila later I felt better than I had in a while. Alcohol cures all. And while no sex resulted from my inebriation, I realized something: here I was, plastered, hadn't paid for a thing, all in front of my teacher. It seemed wrong.

Flash forward to the next day of cocktails at the Algonquin. Too much drinking again, this time martinis, this time with my mother. She had begun to tell me about how she recently got in touch with an old college mate who now does the makeup for "All My Children". She relayed to me how they used to fawn after the same bisexual guy in school. My mother would even smoke to impress him (though she never inhaled). Again, aside from the nausea, dizziness and mediocre piece of theater we ended up seeing, I felt wrong.

Maybe it's just the onset of adulthood, realizing that everyone is more or less a rather complex person whose identity reaches far beyond your perception. But, nevertheless, it is alarming when the barriers break down, considering how much you thought you knew about a person, let alone your purported role models.

Philological Philanthropy

THE PHILANTHROPIST

By Christopher Hampton; directed by David Grindley; sets by Tim Shortall; costumes by Tobin Ost; lighting by Rick Fisher; sound by Gregory Clarke; dialect coach, Gillian Lane-Plescia; associate artistic director, Scott Ellis. Presented by the Roundabout Theater Company, Todd Haimes, artistic director. At the American Airlines Theater, 227 West 42nd Street, Manhattan, (212) 719-1300. Through June 28. Running time: 2 hours 10 minutes.

WITH: Matthew Broderick (Philip), Jonathan Cake (Braham), Anna Madeley (Celia),Steven Weber (Donald), Tate Ellington (John), Jennifer Mudge (Araminta) and Samantha Soule (Elizabeth)

Tuesday, May 19, 2009

Do I?

Friday, May 8, 2009

There's no Business like Show Business.

The official end to the awards season was last Thursday, and the Tony nominations are out. The Seagull was horribly overlooked, and for some reason Rock of Ages racked up a bunch of nominations (including Constantine Maroulis nabbing one for acting). Billy Elliot unsurprisingly garnered the most nominations, not only because it's an adorable little story with great production values, but also because it's the only good musical that opened up this year that seems to be steering Broadway more towards "Vegas", a detraction that producers seem to like because it means higher ticket sales. Nevertheless, I give my regards to the three "Billys": Trent, the sweet one I sorta know, the token ethnic one, and the bitchy one. They all got one nomination for Lead Actor, and honestly that tickles me. Like, they're each one third of an actual person. And, well, let's face it, that's being a little generous with children in regards to their humanity. Anyway, continuing, Waiting for Godot and Mary Stuart were recognized, both getting the Best Revival nod, and so on and so forth. Exit the King got little recognition, sadly, and cult favorites like [title of show] were overlooked, but who really cares? The New York Times pointed out that among the nominees were mostly shows that are still running; which, of course, now being honored with these nominations, means that they can continue to run a little longer due to the press they are getting. And, so, the glaring light of commerce can be shone upon the Great White Way.

Ruined, a fabulous Off-Broadway play by Lynn Nottage, (which I unfortunately missed an opportunity at seeing but have boned up on by reading everything about it) is not among the nominees of the Tony Awards, despite winning the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. That seems a little strange, no? Well, it's not. The Tony Awards have long been discriminatory, and, in recent years, it has made less and less sense. As of now, with fabulous productions not only Off and Off-off Broadway, but nation-wide, it's perplexing that the Tony Awards, arguably the highest honor in the Theater, still remains limited to about 40 productions. Although, now, it's not hard to see that its prestige is washing away, and the awards seem less like accolades praising great artistic achievements and more like the producers patting themselves on their backs for making a lot of money this season. When did the Tonys become the Grammys?

It's just a shame a show is discriminated against merely because of its location/producers, and it’s irritating how much credit they get in this industry. Not to devalue them, because certainly no show would exist without good producers, but all they really contribute is money. Of course, this being America, Theater is a business, so a profit is all that matters in the end. Sure, its a double-edged sword, a great show that accumulates no revenue is unsustainable, and a horrible show that's a cash cow can run for years. Nevertheless, Theater is still a very elitist field, and instead of it getting either all fussy and pretentious or mediocre with a universal appeal, they should just take the stick out of their asses and celebrate talented playwrights who want to enlighten as well as entertain; it shouldn't be about the money or drawing in "different crowds" or what have you. And it certainly shouldn't be about glorifying the producers more than the creative team and actors, because that's what we're watching, not checks being signed.

Tuesday, May 5, 2009

Raining Queen.

Theater Review|'Mary Stuart'

During this inclement week of downpours and cloud-strewn skies, I found myself depressed. Not because of the weather, no, but because I was missing out on it. I have always loved the rain, the refreshing tranquility that comes from feeling beads of water massage my entire body. For a long time I thought this was odd, the fact that I have never owned an umbrella, until I saw the incredible revival of “Mary Stuart” at the Broadhurst Theatre, which opened April 19.

The titular character of Schiller’s classic, played by Janet McTeer reprising her role in the London Production, celebrates her freedom from prison in a spectacularly simulated rainstorm on stage, dancing and acting like a child after a wrongful imprisonment by her cousin, Queen Elizabeth I. The play is a constant battle between the two Queens, despite them only meeting once (but what a meeting!). While that little anomaly never did happen in real life, the rest is accurate; Mary, Queen of Scots, being the last legitimate child of King James V, sees herself as the rightful Queen of England, as Elizabeth was the daughter of King Henry VIII and Ann Boleyn, which, of course, means she’s a bastard. In the eyes of the Catholic Church, anyway. England, however, is a Protestant country now, with the Pope being viewed as their mortal enemy. I seem to have much in common with Elizabeth as well.

That’s wherein the drama lies. Two Queens bound by blood and rank, share as many similarities as differences. The cold, rational, selfish Elizabeth, deftly portrayed by Harriet Walter, serves the perfect complement to Mary, the earthy, downtrodden Queen supported in England only by a band of rebels. Among these rebels is Mortimer, played by Chandler Williams, whose infatuation with Mary Stuart leads to hysterics and destruction. Bouncing back and forth between the struggles of the two women (and in fact the men) the play examines not only political struggle, but personal struggles as well.

The production is seemingly flawless and entertaining, with a spectacularly sparse set design by Anthony Ward and highly emotional lighting and sound. The rich costumes of the two women, also by Mr. Ward, certainly do not disappoint in any way. And the clever dressing of the men in more contemporary garments adds intelligence to a production that can easily be classified as a “costume drama”. It’s the mark of a good designer that every choice has a narrative thought and meaning behind it, not just an aesthetic one. These spectacles, while certainly enhancing to the play, are merely the cherry atop the sundae; it would have been just as rewarding to see the two Queens duke it out with only their acting skills.

It is the now iconic scene that opens up the second act that makes this production of Mary Stuart; two highly concentrated personalities finally have a confrontation, one that brings more ruin than the torrential storm. There are few words that are good enough to describe the emotion felt by the audience, and none that can describe the interaction between the two Queens. It is simply something that needs to be watched.

MARY STUART

By Friedrich Schiller; new version by Peter Oswald; directed by Phyllida Lloyd; sets and costumes by Anthony Ward; lighting by Hugh Vanstone; sound by Paul Arditti; technical supervisors, Aurora Productions. A Donmar Warehouse production, presented by Arielle Tepper Madover, Debra Black, Neal Street Productions/Matthew Byam Shaw, Scott Delman, Barbara Whitman, Jean Doumanian/Ruth Hendel, David Binder/CarlWend Productions/Spring Sirkin, Daryl Roth/James L. Nederlander/Chase Mishkin. At the Broadhurst Theater, 235 West 44th Street, Manhattan; (212) 239-6200. Through Aug. 16. Running time: 2 hours 30 minutes.

WITH: Janet McTeer (Mary Stuart), Harriet Walter (Elizabeth), Tony Carlin (Courtier/Officer), Michael Countryman (Sir Amias Paulet), Adam Greer (O’Kelly/Courtier/Officer), John Benjamin Hickey (Earl of Leicester), Guy Paul (Courtier/Officer), Michael Rudko (Count Aubespine/Melvil), Robert Stanton (Sir William Davison), Maria Tucci (Hanna Kennedy), Chandler Williams (Mortimer), Nicholas Woodeson (Lord Burleigh) and Brian Murray (Earl of Shrewsbury).

Sunday, April 26, 2009

He Never Arrives, BTW.

The revolutionary Beckett play, considered a key piece in dramatic literature, is as interesting as it is evasive. Wrapped in repetition and monotony, the Roundabout Theatre’s new production now playing at Studio 54 makes one leave the theatre with more questions to be answered than might be expected. And isn’t that the point of Theater?

WAITING FOR GODOT

By Samuel Beckett; directed by Anthony Page; sets by Santo Loquasto; costumes by Jane Greenwood; lighting by Peter Kaczorowski; Presented by the Roundabout Theater Company, Todd Haimes, artistic director. At the Studio 54 Theatre, 254 West 54th Street, Manhattan; (212) 719-1300; Through July 5th. Running time: 2 hours 15 minutes.

WITH: Nathan Lane (Estragon), Bill Irwin (Vladimir), John Goodman (Pozzo), John Glover (Lucky), Cameron Clifford (Boy), Matthew Schechter (Boy).

Thursday, April 23, 2009

The Intelligent Blogger's Guide to Theatre and Criticism with a Key to Kushner.

The Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, Minnesota is currently having a Tony Kushner celebration. In addition to staging his musical, Caroline, or Change, and a collection of short plays (playfully titled "tiny Kushner"), the theater is premiering his latest play, The Intelligent Homosexual's Guide to Capitalism and Socialism with a Key to the Scriptures, directed by Michael Greif (of Rent and Grey Gardens fame, who also did a fabulous production of Romeo & Juliet two summers ago in Central Park and is currently working on next to normal.)

Thursday, April 9, 2009

How to Shape the Law

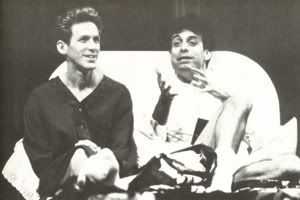

I was thumbing through "Angels in America" for the kazillionith time recently, and began to wax poetically on ethics. “The shaping of the law, not its execution.” Louis ponders the nature of justice in bed beside his lover, Prior. “…it should be the questions and shape of a life…which matters in the end, not some stamp of salvation or damnation which disperses all the complexity in some unsatisfying little decision…”

It’s an interesting supposition to consider. It paints in my mind the image of the tarot card entitled “Judgment”; an angel, eclipsing the horizon, blowing a horn, resurrecting a legion of corpses before the final judgment of Christian tradition; an image that symbolizes this “stamp of salvation or damnation” in a religious life. For the large sect of us who do not subscribe to such an image based on religion, does our secular life hold to similar strictures of judgment? Can our peers judge us in that same way? Can we be damned by society if we do not beg forgiveness for an action? For those of a particular faith, it can be simpler; for others, it cannot.

As the aging Rabbi Chemelwitz points out: “Catholics believe in forgiveness, Jews believe in guilt.” In the Catholic faith, one can commit any transgression he likes, so long as he confesses and repents before his life is over. An entire life composed of immoral, disparaging acts can be rectified in one sitting, thus, the components which make up said life mean little if, before the final judgment is enacted, forgiveness is given. For atheists and agnostics, this is not a scenario in which we can easily place ourselves.

It appears, then, that Louis’s theory is a logical and easily accessible one, especially to people who do not subscribe to a religious faith. Our lives should be judged by the broad spectrum of our actions, by the sum total of what we do and what impression we leave on the world, not one thing we do, whether it be good or bad.

The theory does open up some doors, though, of evasion and disregard towards the transgressions we commit, because to Prior, “…[Louis’s theory] seems to let you off scot-free. …No judgment, no guilt or responsibility.” Does a life of good actions balance out a single misdeed? What if, say, a charity worker commits a murder? If she sacrificed her life helping and aiding hundreds of lives but destroys one, shall she be eternally damned? She can forgive all she wants, but her actions cannot be changed.

Perhaps an amalgam of sorts is in order; perhaps forgiveness is an integral part of an already broad life. Actions cannot be changed, but attitudes can. Perhaps we need to enact the “neo-Hegelian, positivist” sense of the world Louis holds so dearly, confirming that progress, while suffused with pain and struggle, is always for the better. Perhaps we will not get stamped at the end of our lives, but we shall try our hardest to live good ones, no matter how difficult it may be.

[pictured: Joe Mantello and Stephen Spinella, Original Broadway Production]

Sunday, April 5, 2009

The Riddle of Ritalin

DISTRACTED

By Lisa Loomer; directed by Mark Brokaw; sets by Mark Wendland; costumes by Michael Krass; lighting by Jane Cox; original music and sound by David Van Tieghem; projection and video design by Tal Yarden; associate artistic director, Scott Ellis. Presented by the Roundabout Theater Company, Todd Haimes, artistic director. At the Laura Pels Theater, 111 West 46th Street, Manhattan; (212) 719-1300. Through May 10. Running time: 1 hour 45 minutes.

WITH: Peter Benson (Dr. Daniel Broder/Allergist/Dr. Jinks/Dr. Karnes), Shana Dowdeswell (Natalie), Lisa Emery (Vera), Natalie Gold (Dr. Zavala/Waitress/Carolyn/Nurse), Matthew Gumley (Jesse), Mimi Lieber (Sherry), Aleta Mitchell (Dr. Waller/Mrs. Holly/Delivery Person/Nurse), Cynthia Nixon (Mama) and Josh Stamberg (Dad).

Tuesday, March 31, 2009

Cool Hand Fluke

Sitting upon Riverside Drive at 140th Street is an arresting sight: a large, gothic, classically designed building, once a Catholic Girls’ School, now owned by the Fortune Society. It is nicknamed “The Castle” and is a refuge for formerly incarcerated people. Of the 700 or so boarders who have drifted in and out of it, four noteworthy ones, in conjunction with director David Rothenberg, have began telling their woeful stories of trauma and crime at the New World Stages. On the face of it, a production with only four chairs as a set, no traditional dramatic structure and a cast of former criminals locked in a basement with an unwitting audience would not seem too successful; shockingly enough, it works.

The quartet—Cassimo Torres, Kenneth Harrigan, Vilma Otriz Donovan, and Angel Ramos—speaks directly to the audience, weaving their personal stories in short, succinct bursts of monologue together to form a larger narrative that addresses not only the successes and failures of the prison system in the United States, but of the conflict that arises from societal pressure on personal choices. It is interesting for us to see how Ms. Ortiz Donovan, a Long Island suburbia native, and Mr. Torres, a homeless junkie, could end up in the same safe haven for ex-convicts. Ms. Ortiz Donovan, a self-conscious girl, was seeking approval from her peers, all of which came to a head when she became a user and dealer of cocaine. Drugs were Mr. Torres’s weakness as well; he graduated from the triad of alcohol, weed and acid to crack-cocaine and heroin in only three years. Coming from a broken home, he was subjected to abuse in the centers he and his brother were shipped to after his mother was admitted to the hospital. In spite of their very different upbringings, the two failed to resist to the temptations around them, and ended up behind bars.

With drug abuse as the common thread of their convictions, it’s fascinating to see how people from different walks of life could assume the unenviable position of inmate in the New York State Prison system. Ms. Ortiz Donovan repeatedly makes the statement that her choices solely contributed to her incarceration, while the men are less eager to blame themselves. Mr. Harrigan, for example, repeatedly paints the grim picture of his life as one of the factors that landed him in the big house. His disturbing image of a woman hanging from a telephone pole just outside of his home is but one example of the terrible environment in which he was reared. So where can one assign responsibility of fault for delinquency? When can we draw the distinction between offenses stemming from personal depravation to those influenced by peer pressure? One crime, one indiscretion by a person is what is seen by a court, by a judge, but said person’s actions are never entirely his own. Wouldn’t Mr. Torres’s absentee father hold some iota of blame in his drug crimes, considering the (Ann Coulteresque) statistic that fatherless children are apparently 10 times more likely to abuse chemical substances? But he is not punished, only Mr. Torres is. These are the questions that the audience is provoked into contemplating during a performance of “The Castle”, moving us all into some sweep of emotional response.

Each member of the ensemble was moved to tears at one point during their personal accounts, legitimate tears of pride, sadness and strength that could outweigh any Oscar winner’s performance, if for no other reason than because they were real. I found it refreshing to see such a genuine display of emotion on stage, certainly not because I wish that all actors would abandon their craft (what would become of the theatre‽), but it is, admittedly, a delight to see such awe-inspiring performances that are unequivocally rooted in the sprawl of real life rather than weeks of rehearsals. Of course, that’s not to say some additional prepping would have been a sensible action in this production; each of the performers committed some impropriety during the play, ranging from late delivery to trying too hard to elicit a laugh from the audience. These missteps are easily overlooked, however, when considering the overall effect the play can have on a person.

The apparent success of “The Castle” may be rooted in the deeply moving struggles of the quartet, the discouraging realization that prisoners have souls, and that we are all at risk of penalization. Or it may simply be luck. Whatever the explanation may be, this piece of documentary theatre inspires and enlightens, even when it takes itself too seriously, or shows its rough edges.

Wednesday, March 4, 2009

Video Killed the Drama Star

Theater Review|"Coming of Age in Korea"

The stage is set at the Castillo Theatre with a haphazard, industrial façade constructed of putty-colored planks of wood and sheet metal nailed against a stark purple wall. Various white Hangul are stenciled across the backdrop with the year, 1954, prominently displayed at the center of the proscenium. Amidst this cold, rustic stage, quite discordantly, is a large movie screen. That’s where the trouble began.

“Coming of Age in Korea” follows the life and times of three outcast soldiers in the Korean war, one Jewish, one Black, and one Hispanic, who are singled out by their colonel not only for their respective races, but because they have not yet contracted Chlamydia or any other venereal disease from a Korean prostitute like the other soldiers have already.

The story is told in this production of the 1996 Fred Newman musical through the tense combination of live performers and film sequences; the main plot is expelled in shaky, home-movie quality shots of the character’s experiences in the Korean War, while their internal conflicts are presented live through song and interpretive dance. Testing the limits of how the two media play off of each other, the audience experiences a frustrating disconnectedness from the start as we view a 40th reunion of the characters on screen, and then on stage given a retro pastiche musical number concerning pop culture in the 50’s, which seems to lead us no where in the story as the singers and dancers trot around in EmilieCharlotte’s costumes, which try hard to suggest historical accuracy and winsome eye candy, but are limited by a small budget and homemade craftsmanship. Suddenly, we’re thrown back into the film, and so the tug-o’-war continues for two hours. No matter how hard we try to concentrate on the story, we are quickly swatted away by crude pageantry, which is a shame, because a story was all the play needed to carry itself.

Upon entrance to the theater, guests are handed an article from the New York Times concerning a dreadful historic episode where during the War, the Korean government coerced their women into prostitution to appease American soldiers. Looking over the article, I worried how the issue would be handled in the play, if it would take sides, and if there would be a conclusion to these events despite the fact that there was none in real life. Apparently, though, that’s not what the play is about. It may just be a simple coming of age story, a theme that hardly holds any weight and has a hard time provoking any emotion from the audience. Only in the supersaturated scenes of exposition concerning the Korean girls, Suzie and Little Kim, do we see the story line pushed further. Finding a through-line from the unrefined lyrics in the early song “The Clap” to the painful “Little Kim’s Song” to the eventual sharp, staccato scenes of action that lead us to a climax, the play had enormous potential to tackle this intriguing issue, but apparently, it doesn’t fail to do so; it refuses.

Distracted by the contrasting media presentation, the play insists upon the non-avant-garde styling, which muddles up the story as well as the acting. Whenever a live performer sings, headlined by the decent efforts of Melvin Chambry, Jr. and Aja Nisenson, we are sometimes unclear of who exactly they are supposed to be, in part because of their race (Philip M. O’Mara, a young Asian man, plays the very Jewish Greenberg once or twice) and in part by the hazy, repetitious lyrics which give only vague clues as to which character is pouring his or her heart out.

The movie isn’t much clearer in terms of plot or character; Walt Shelton (Chima), one from the trio, occasionally steals the spotlight, from occupying the subject of the Act One finale to the small subplot concerning his penalization for being absent without leave, but immediately the focus shifts to Frankie Greenberg (Evan Shultz) and Little Kim’s demise later in the second act. Shultz displays skill as an actor in this production, albeit comically, through his contorted expressions and his shrill New York accent, however his histrionic approach to the material is perhaps best suited to the stage, not the screen. Although the two scenes he had with his love interest, Little Kim, were genuine and pleasant, they were not enough to convince us that they fall in love in a very short amount of time.

Certainly quick romances aren’t unorthodox, especially in theater, as in “West Side Story”, whose action takes place in one day. However, the love between Tony and Maria is believable to us because the entire story hangs off of that fact, so no unrealistic time constraint deters us from the play. In “Coming of Age in Korea”, Greenberg’s “love” for Little Kim comes on too late and ends too early to ever be considered real.

The play is riddled with these frequent lapses from reality in which it declares its theatricality, including, for instance, a line where a peripheral character comments that the protagonists won’t be friends in 40 years, despite us knowing that they will. These self-referential hiccups, which some dilettantes might deem “Brechtian”, are realistically just an elbow-in-the-ribs-style joking with the audience; the play is not so much an interpretation of reality but, rather, an interpretation of such a concept. While directors Desmond Richardson and Gabrielle L. Kurlander are not intentionally letting the audience glean a particular message about racism or war or the governmental duress of local women into prostitution, it would appear that the play (or movie) is at the very least trying to do exactly that.

Accordingly, we as the audience are left in an abrupt quandary. It is as if we are looking at a stained glass window, a mélange of spectacle, music and film, with the dim light of a thought trying desperately to break through. By the end, though, we find out that isn’t going to happen. As we applaud an awkward curtain call of the filmed performers, our praise wasted on discarnate actors, we are reminded finally that unless properly handled, the stage is best suited to drama or film, not both.

COMING OF AGE IN KOREA

Book & lyrics by Fred Newman; music by Annie Roboff; directed by Gabrielle L. Kurlander & Desmond Richardson; sets by Joseph Spirito; costumes by EmilieCharlotte; Presented by the Castillo Theatre . At 543 West 42nd Street, Manhattan. Through March 1. Running Time: 2 hours.

WITH: Chima Chikazunga, Natalie Chung, Emily Gerstell, Andrea Harrison, Amanda Henning-Santiago, Kaitlin Hernandez, Jim Horton, Brittney Jensen, Jaiwen Liang, Christine Komei Luo, Casey Mauro, Leroy Mobley, Brian Mullin, David Nackman, Lynnette Nicholas, Aja Nisenson, Vigdis Olsen, Philip M. O'Mara, Johanny Paulino, Reynaldo Piniella, Esteban Rodriguez-Alverio, Evan Schultz, Melvin Shambry, Jr., Isaac H. Suggs, Jr., Jeff Wertz.

Monday, February 23, 2009

New York Collections: Project Runway #1

Sunday, February 22, 2009

New York Collections: Project Runway #2

Saturday, February 21, 2009

New York Collections: Project Runway #3